ACS CAN Comments to CMS re: Montana 1115 Waiver

ACS CAN submitted comments to CMS opposing Montana's 1115 waiver application to implement work requirements and premiums in their Medicaid program.

Medicaid is a critical source of health insurance and coverage for more than 77 million Americans, including people with cancer who rely on the program for prevention, timely detection, treatment, and survival. The 2025 budget reconciliation bill makes significant changes to key Medicaid funding mechanisms like state-directed payments and provider taxes, which are expected to reduce states’ ability to finance their Medicaid programs. This factsheet outlines what these changes mean, the projected financial impact on states, and consequences for patient access to cancer care.

Medicaid Funding Mechanisms: Provider Taxes and State Directed Payments

The Medicaid program employs a joint financing mechanism that relies on both state and federal funds. To help finance the non-federal portion of Medicaid spending, states are allowed to utilize provider taxes; these taxes are incurred by providers (hospitals, nursing facilities, etc.) in a given state, usually as a percent of provider revenues or a flat tax based on other quantitative metrics relating to provider characteristics. Provider taxes are an important funding mechanism for Medicaid, in part because this tax revenue is money the state can use to draw down the federal match and fund its program – and it’s a tax that providers, an important constituency in Medicaid policy, generally support.

Another funding mechanism for Medicaid involves state-directed payments (SDPs). These payments mandate managed care organizations — integrated health systems providing health care to members by reduce costs and improve quality — to financially compensate health care providers by raising provider payment rates and inherently increase patient access to and the quality of care. SDPs are approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), but states have the authority to govern how MCOs structure payments to providers (usually consistent across a given class of providers).

Changes in the 2025 Budget Reconciliation Bill

The new federal law contains three sections that make major changes to how states use these funding mechanisms. Section 71115 mandates freezing pre-existing provider taxes at their existing levels and prohibits increases in new provider taxes or existing tax amounts. Section 71115 also targets safe harbor exceptions, where states had the authority to leverage hold-harmless arrangements to collect provider taxes so long as they were not more than 6% of the provider’s net revenues. Hold-harmless agreements are a mechanism by which states can tax providers that receive Medicaid funding higher than providers who do not. While these agreements were largely dissolved in 1993 in favor of uniform taxation rates, safe harbor exceptions allow some hold-harmless agreements to persist. The bill retains the 6% cap on non-uniform provider taxes for non-expansion states and exempts long-term care facilities, but reduces the threshold to 3.5% in 0.5% increments beginning in fiscal year 2028 for expansion states.

Additionally, Section 71116 limits the scope of any new SDPs to 100% of Medicare rates for expansion states and 110% of Medicare rates for non-expansion states. Medicare payments rates tend to be approximately half of the average commercial rate for many services. Under the legislation, states that have existing SDPs that are above Medicare rates must reduce payments in increments of 10 percentage points each year starting in 2028, until they reach 100% of Medicare rates in expansion states and 110% of Medicare rates in non-expansion states.

Every dollar a state spends on its Medicaid program is matched by the federal government at a certain rate (between 50% and 83% as mandated by law according to the state’s federal medical assistance percentage [FMAP]). Therefore, lowering state spending on Medicaid also lowers federal spending – and limiting states’ usage of SDPs and provider taxes to fund their Medicaid programs is projected to lower state – and consequently, federal – spending on the program. A policy analysis conducted by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates a $191 billion reduction in Medicaid spending due to limitations on provider taxes and a $149 billion reduction as a result of changes to SDPs.

Finally, section 71117 changes the requirements for provider tax uniformity waivers. In the past, states have been allowed to finance the non-federal portion of Medicaid expenditure through sources like provider taxes if those taxes were broad and uniform. These uniformity rules could be circumvented through waivers as long as the taxes were generally redistributive, but changes in Section 71117 mandate that many currently permissible tax structures like those used for managed care organizations will no longer qualify for waivers – and therefore no longer be allowed. In response to the limitations imposed by Section 71117, the CBO has estimated a federal Medicaid spending reduction of $35 billion over 10 years.

Changes to SDPs and Provider Taxes Will Severely Impact Most States

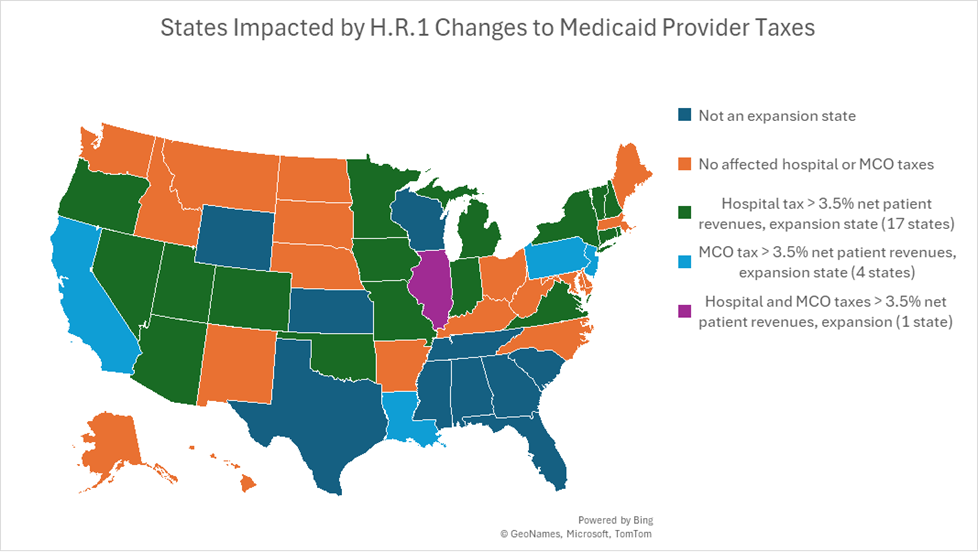

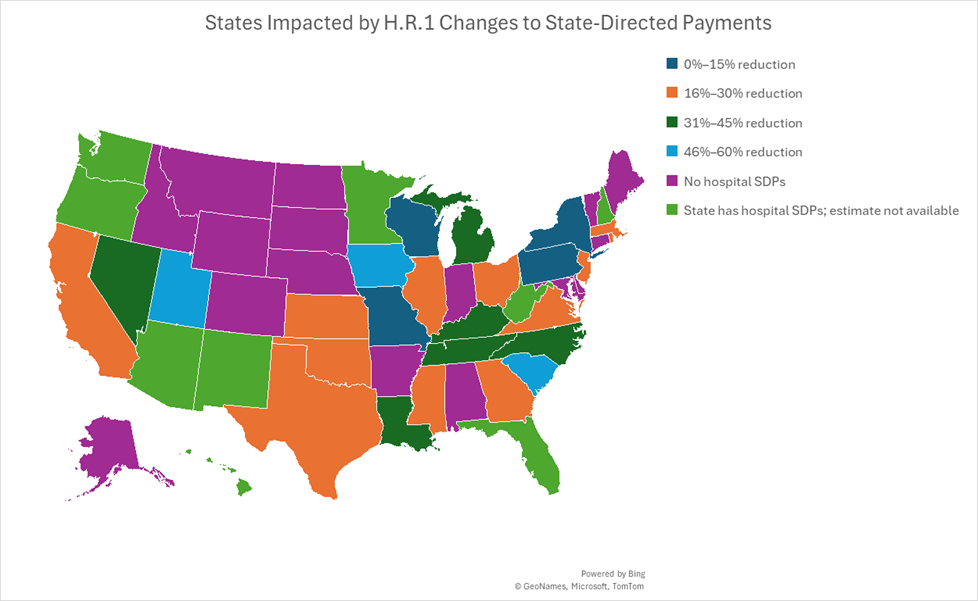

Expansion states in comparison to non-expansion states are disproportionately impacted by caps on provider taxes. As seen in Figure 1, 17 expansion states have a hospital tax greater than 3.5% of net patient revenues, 4 states have a MCO tax greater than 3.5% of net patient revenues, and one state has both. Expansion states will have to lower their provider taxes, which in turn will reduce federal and state Medicaid spending. Figure 2 highlights the estimated reductions in Medicaid payments to hospitals when SDPs are limited to 100% of Medicare rates, showing the greatest reductions for non-expansion states like Wyoming, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Figure 1. States Impacted by H.R.1 Changes to Medicaid Provider Taxes, Source: KFF

Figure 2. States Impacted by H.R.1 Changes to State-Directed Payments for Hospital Payment Reductions, Source: Commonwealth Fund

Medicaid Funding Cuts Will Harm People with Cancer

Funding restrictions related to provider taxes and SDPs could have significant downstream effects on access to care, particularly for cancer patients and survivors. Medicaid plays a critical role in ensuring early detection and timely treatment of cancer by providing access to health care insurance and covering preventive healthcare services like immunizations, cancer screenings, and counseling for self-management of chronic illness. One-in-ten adults with a history of cancer in the United States rely on Medicaid for health insurance,[1] and 1-in-3 children newly diagnosed with cancer in the U.S. are enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Cutting Medicaid funding threatens the lifeline of health insurance coverage that Medicaid provides to these families.

Additionally, cutting the amount of Medicaid funding providers receive will make it harder for Medicaid plans to maintain their provider networks. CMS sets network adequacy standards for Medicaid managed care organizations; these standards refer to time, distance, and provider density guidelines to ensure that managed care plans offer sufficient access to essential providers and services for the patients they serve. For cancer patients and survivors, access to a coordinated team of specialists and coverage of expensive treatments is essential for positive health outcomes. However, capping SDPs and limiting provider tax flexibility may result in states cutting reimbursement rates, leading providers to scale back services, reduce Medicaid patient slots, or stop taking Medicaid patients entirely.

ACS CAN Position

It is vital that Medicaid remain a lifeline to comprehensive, affordable health coverage for people with cancer, survivors, and people in need of preventive and screening services. ACS CAN opposes policies that threaten this coverage, and we strongly opposed the health provisions of the 2025 budget reconciliation bill because they represented the largest cut to the Medicaid program in its history. ACS CAN will closely monitor implementation of this legislation at federal and state levels, including how changes to Medicaid funding mechanisms impact Medicaid coverage, covered services, and enrollees.

[1] 2023 National Health Interview Survey data. Analysis performed by American Cancer Society Health Research Services, December 2024.